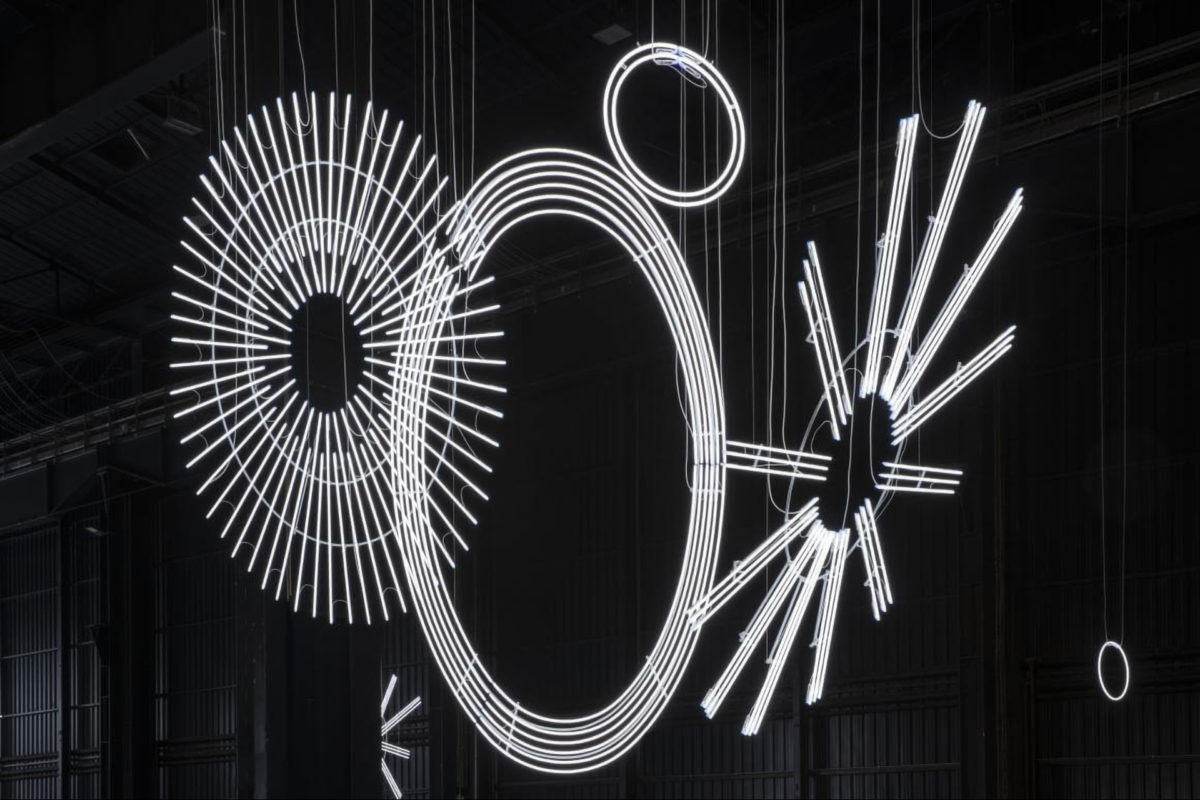

The largest-ever solo exhibition of Cerith Wyn Evans at HangarBicocca, Milan. In Lampoon’s February 2020 issue, the artist spoke to Rome-based curator Cornelia Lauf

The role of art as a form of cultural diplomacy in the 21ist century

Cornelia Lauf: Your project as a whole has been crafted for Italy, a country you have worked in numerous times, and which you clearly love. At the same time, the exhibition at Hangar Bicocca, entitled The Illuminated Gas… refers to the Large Glass artwork by French artist Marcel Duchamp, swirls in neon by Italian painter Lucio Fontana, and the palm trees of Belgian artist Marcel Broodthaers. At the same time, the exhibition has the dryness of a very British, if not the lyricism of a Welsh production. In short, a deeply European show, but one that would not have been possible without the scale or media choices of American artists of the last century. such as neon, or the scale of an Alexander Calder mobile. What do you think about nations and geographies, at this point in the 21st century, and about the role of art as a form of cultural diplomacy? We have to think about the fact that we are in a time of great strife.

Cerith Wyn Evans: We have to think we are in a moment of global hyper-capitalism, where identities have been reduced and distilled and we are dealing with an ecology of commodities. It’s hard to say this outright, and I’ll say it guardedly, but I think we need to get into a concept of the resisted. That is to say that traditional narratives of classical perspective, or technological prowess have to be superseded, and we need to realize that we are in an epoch of the realization of Guy Debord’s ‘Society of the Spectacle’. Art is a possible form of resistance, a way of putting into perspective a series of codes, of pointing to power structures. We need to liquify phallic notions of power. Think transversally. Create a kind of psychic liquefaction, and work out an ‘eco-poetics’. This is the time to think transversally, to think in terms of transport.

CL: Just think of someone like Pieter Paul Rubens, who was mediating for the Spanish court, and creating ephemeral architectures that expressed political concepts. Could you conceive of yourself designing such objects or structures, in the name of cultural diplomacy?

CWE: Would I be interested to think in a more overt political sense? Art is a deep-seated homeopathic tradition. There are certain ramifications to being a political advisor. Do I think there should be a Greta Thunberg in art? And would I put myself out there to be in politics? We are in a different time than the seventeenth century. To think about this, we need to look at the history of democracy, of capitalism. And maybe think of a resistance to that. Perhaps there is a power through intimacy, through nuance. A poetics in subtlety.

CL: I felt that your show was both an exercise in something authoritative but at the same time, a dismantling of the authoritarian. You pass through the exhibition, going from the first area that has columns of light, to hanging mobile works of text on passing in which the spectator can really interpret them as he or she feels best. The show is monumental but also allows for a kind of private rêverie and introspection. You allowed intimacy despite the monumentalism.

CWE: Well, mega-spectacles don’t really interest me per se, as it is a kind of presumptuousness that is not for me. I feel one can achieve much more through the poetics of intimacy.

Architecture by artists and the prejudice of using artists’ designs for urban planning

CL: You are referencing Classical columns in that first section of the installation, and there certainly is no more ‘Italianate’ object than the pillar studied by Vitruvius, Serlio, and Palladio. The column stretches back through time to Greece, Egypt, Babylon. I feel you channel all those epochs in a kind of architectural language that could clearly be applied to skyscrapers and city skylines. How do you see architecture by artists and why is there a prejudice in the modern era against using the designs of artists as the basis of urban planning?

CWE: Pillars can be seen as going back to the prehistoric era, they simply held up buildings, and I am using the column as a form of grammar, a kind of commodification, in a material which is light. I am interested in the utopian purposes of art and the swap between form and function, when one becomes the other, the dichotomy between liquid and soft hierarchies. It’s time that rigidity of definitions ends and a kind of trans-verse, or transverse, enters the vocabularies.

CL: This can apply also to sexuality, which as you see today, is a much more elastic concept.

CWE: Yes, there is a thirst for fluidity, for a “trans” position. This applies also to the notion of time. I am interested in people who develop ideas through time, and ideas about time. About the in-between, about travelling from one place to another, about inter-spaces. We have to change thinking to a notion of production that is about process rather than product. The experience is the event, the process.

CL: This is one of the most successful shows ever mounted at the Hangar Bicocca. How do you attribute this success?

CWE: I am really wary of populism or measuring myself in terms of success. I never judge something by “bums on seats” calculations. You can see all the effects that populism is having on the world. What is important is how people are stimulated. How they are given a different form of access. Oscar Wilde once said that if his work was becoming popular that there must be something wrong. I try to be alert, not rest on my laurels.

Lampoon reporting: Cerith Wyn Evans ‘environment of intimacy’

CL: You fabricate an environment of intimacy, can you speak a bit more about that?

CWE: I just came back to the Hangar Bicocca, after an absence, and had a chance to reconnect with the work. To get the “hic et nunc,” haptic qualities, all over again. The phenomenological qualities of the show. The heating system. The lightbulbs that may have been out. The changes in atmosphere and temperature. It was all changed, though it was all the same.

CL: In numerous articles, and in the press conference, one could sense that the Hangar Bicocca Director, Vicente Todoli, relished the chance to “fight” against a living artist. Even though it was curated by two curators, I sense a kind of duel going on there between you and him. It’s very different than when the artist is no longer alive, and the curator can install according to their own inner poetry. How was that collaboration and experience?

CWE: I am really pleased that the show has had this great effect and grateful to the Hangar Bicocca for making the experience free of charge. People can get on the subway or bus and come up there. It is like going to a park, or a garden. I have a chance to hear conversations, where the art is a kind of backdrop. It assuaged my sense of guilt over doing such a monumental project. The exhibition is really meant for a stroll, a promenade, and not the kind of march through an enfilade that is programmed… It’s not about being an exhibition where you see the juvenilia, the early work, then progress on, and end with the black paintings.

Cerith Wyn Evans relationship with fellow British artists

CL: Can you talk a bit about the many references to friends, less stated, perhaps than your more overt homages and tributes? What I admire in your work is this effortless ability to quote. You cite writers and musicians, from James Joyce and Marcel Proust to Chopin, from Erik Satie to Karl-Heinz Stockhausen. Yet, though you are beloved by your artist friends, you rarely get ‘art historical’ in a more immediate sense.

What is your relation to your fellow British artists? I see nods to figures such as Angela Bulloch, or even Jonathan Monk, if not a great affinity. You and Ryan Gander both speak about time in much of your work. And I think Liam Gillick and you share a lot in your use of quotes and light. I love the piece Sutra, for example, which refers to your clock pieces and to Felix Gonzalez-Torres. I guess I am attracted to that generation of artists that uses quotation overtly.

CWE: It is a form of camaraderie, a kind of family, a system of allegiances. A type of cartography, and shared notion of citation and quotation, where we are brothers, in a sense. It’s a form of incarnation of the context that drives one to the quote. It’s like an Archimedean point in space, that constructs a geometry that becomes a dialogue. It broadens one’s own experience, and allows one to experience a contextual structure.

CL: The only figure I see really wading in there and getting really personal is Ryan Gander – he is the only one who can quote his daughter’s fingerprints, for example, in an artwork. A hundred or so years ago, you would have had James McNeill Whistler painting his mother, but today, you can’t really become personal this way, without being maudlin or sentimental. What’s that about? Jonathan Monk has referenced his father, but really there are few artists who get personal in their work.

CWE: I guess a crude analogy could be that this is a kind of abstract familial sense, a kind of Mom and Dad in art… Gander is daring and able to become personal because he is micro-aware of all the codes, and can loosen the stitches. He is opening up a new field, in fact.

CL: Family. You have spoken to me of the relation between your parents and the relation to you. You have created a family of friends and associates, and in all your print publications, you weave together people that are dear to you in a kind of evolving spiral-like way. I know you through Christoph Keller and Peter Pakesch, then I see that you have people like Jonathan Crary and Martin Prinzhorn write. I feel you knit together genealogies of love and affection, of tributes, that range from literary and philosophical ones, to those of the heart. Can you speak a little about emotional currents? What motivates you to create? Emotional alliances? Deadlines? Pressure?

Opportunities as a new territory to explore

CWE: I never found art to be useful as a form of expressionism, or that expressing personal details was a form of truth. How I feel about opportunities is that they are a form of new coordinates, a new territory to explore, a platform that is different, and that one has to situate oneself on. I am at a stage in my career where I am getting a lot of these kinds of new coordinates, and new opportunities, and that is very exciting. White Cube (my upcoming show February 8) is everything but a white cube.

It is a gallery that is not about being a white cube. The context is a form of citation. When I taught Foundation at art school, it was really important to challenge the students, with questions of how we might interrogate students or confuse them with notions of what a site is. I separated out the concept into three notions of the word: sight, cite, and site. I had them analyze phenomena in a transversal way, to change their perception.

CL: The way artists make meaning, is to inhabit the forms of prior artists and hollow them out to the point that they become a new skin. This is then used to create other meanings. It can be adopted in parts, and disguised, but I see it as a kind of absorption in full of the magisterial qualities of prior generations. Once the Italian artist Emilio Prini told me, «Tutto è pronto. Da sempre». In a way you are working on this idea of transmission and also the static quality of objects in time. I noted that one of the images in your press kit was taken by you. To what extent are the photos taken of the installation ‘filmic’ or artistic in themselves? The installation is difficult to capture fully. It feels a bit like the set of Stalker. You almost need a moving camera to capture it.

CWE: There is an illusion of time, and we are really connected to Baalbek, and all is metaphysical. I don’t presume to say I have nailed it down. But art is not entertainment or show biz. And though I’m not one of those people who without shame claim to understand the world, I think I show glances of what it is, what time is. In the catalogue, there are a sequence of images I have borrowed, stolen, and loosely structured in a collection that is edited by the graphic designer.

I have put my own images in there and leave it up to the others to decipher and interpret. I felt a sense of nostalgia at the end, like you were preparing an ode to the decline of the world, the ending of all living things, not only some comment on the Anthropocene. You had the yin and yang of plants, the pine and the palm, if I am not mistaken, and they were dying, starved for light, and water. The installation does not end in death per se, but there is a sense of lamentation. Viewers were silent. The sonorous elements seemed elegiac.

Cerith Wyn Evans

Born in Llanelli, Wales, Wyn Evans began his career in the late 1970s and early 1980s London. He studied at London’s Central Saint Martins and then at the Royal College of Art under British Conceptual artist John Stezaker. After graduating in 1984, he encountered post-punk culture and avant-garde filmmakers active in independent cinema. In the 1980s, he moved away from film and towards sculptures and site-specific installations, presenting his first solo show at White Cube, London in 1996.

References in his work include major figures in 20th-century art, notably Duchamp. One of the most acclaimed British artists, Cerith Wyn Evans now lives and works in London and Norwich. His works have been exhibited in numerous solo shows, including at the Tate Britain, London, Schinkel Pavilion, Berlin, and MUSEION, Bolzano. In 2018, he was awarded with the Hepworth Prize for Sculpture.