An overview on the documentary film that follows François Demachy, Parfumeur-Créateur Dior, in his journey through the area’s milieu, heritage and expertise

Dior Nose: Grasse – François Demachy’s childhood place

Dior Nose documentary. On the coastline of Provence, one finds orange blossoms and mimosas. Centifolia rose, jasmine as well as tuberose thrive at three-hundred meters of altitude. While moving up, at five-hundred meters over sea level, the violet grows best, together with iris and narcissus. Above that, there is wild lavender, broom, and medicinal plants.

Located thirty kilometers north-west of Nice, Grasse’s flora thrives on the specificity of its geographical location. The area’s microclimate, generated between the Mediterranean Sea and the Southern Alps, has led Grasse’s botanical varieties to adapt and bloom through mild winters and hot, wet summers. Combined with a clay-limestone soil, these conditions, therefore, allow Grasse’s flowers to express their scent and fragrance.

In this region, people have been extracting raw materials for four centuries. The art, skill and knowledge involved in making perfumes reign to this day. A city of tanners since the seventeenth century, Grasse has seen its mastery in perfumery flourish together with the custom of scenting leathers. And Grasse is the place where François Demachy spent his childhood. And where he transformed his imagination and curiosity about places, landscapes and people into a profession.

Dior Nose: The art of being a perfumer according to François Demachy

Being born and raised in a family where the sense of smell had the same importance as sight or hearing, Demachy’s connection to the lands of Provence is entwined with nostalgia. He recalls his youth’s summer holidays, in August, by thinking of the smell of jasmine in bloom. «When you are faced with the memory or the reality of a smell that you haven’t smelled in thirty years», Demachy explains, «you are immediately brought back thirty years in the past».

A passion for recording smells is what brings together every perfumer. The profession requires them to refresh their memory on a daily basis, memorizing smells and combinations anew. That does not guarantee that a creation will correspond to what was imagined. It takes, in fact, anywhere from fifteen to fifty ingredients to develop a fragrance.

Grasse, the milieu of a savoir-faire

Making a perfume is a matter of using one’s sensibility and expertise with accuracy and timeliness. Perfume trials are the tools that reveals the distance between the idea of a perfume and the formula the creator has to write down or read to make one. «The worst for us is to think you know», Demachy asserts. Keeping up to date, getting back to the baseline as well as practicing with continuity are the fundamentals of this art. To him, a perfumer is an interpreter. While, Grasse is the milieu of a savoir-faire.

When he wants to develop or modify a scent, he discusses with local professionals and does the trials with them. An opportunity he considers an advantage. Touching the soil, talking to the farmers and being connected to Grasse’s production elevates his practice. Creating an atmosphere is part of the product’s development. Further, being in the site of production allows Demachy to smell and feel an ingredient’s ambiance, that is, its atmosphere. It is Demachy’s way of maintaining a connection to the land and its heritage.

Dior Nose: François Demachy’s professional path

During his apprenticeship, Demachy’s first creation was intended to whet the appetite of bovines so they would eat the fodder. His first actual perfume was Diva, from Ungaro. He made that for his wife, Alexandrine Demachy, working with emotion and seduction. Desire, to Demachy, is the fil rouge of perfume making. As Demachy’s spouse recounts, the perfumer envisions his creations based on the people he meets. «The person comes first and then comes the inspiration», and for him, the challenge is to make a perfume that suits them.

To Jacques Cavallier, parfumeur-createur at Louis Vuitton, the human side is essential in perfume. Everybody has a sensitivity toward smells. «They bring us back to our culture, our identity. It’s what we are made of». Him and Demachy share more than a profession. What ties them is their passion, their knowledge of raw materials, their olfactory education – as they are both from Grasse – and a mission, as they have to create the best possible perfume for their respective houses.

Dior Nose: François Demachy’s perfume making process

Monsieur Dior’s last mansion was Château de La Colle Noire. It stands on a promontory overlooking the plains of Montauroux, at the border between the Alpes-Maritimes and the Var region, about sixteen kilometers south-west of Grasse. At Dior’s headquarters in Paris, Demachy has his office, filled with vials, glass bottles, paper strips, and books. But it is nature where his expertise and curiosity shine. To him, seeing the product in its natural habitat, to see the method and the material, are the basis of the art of perfume. In his eyes a perfumer is an artisan that aims to strike a balance between creativity, intuition, and technique.

In perfume making, the palette is as vast as human imagination. It takes thought and distillation to hone in thousands of raw materials and come up with a concept. Making a fragrance that lasts is like composing a symphony. Notes – in music as in perfume – are the building blocks, the nuclei, that creators use to build a statement or an idea. But it’s the changes in a formula that make a difference in how consumers perceive, relate to, and internalize a fragrance, as in the words of journalist Eddie Bulliqi. That’s where the parallel between music and perfume comes from.

Dior Nose: Perfume industry’s investment in organic practices

«Perfumes are a language everyone understands, but few people can speak», says Demachy. After pruning, weeding, honing the fields for a year, harvest time comes as a reward to Grasse’s flower farmers. Christelle Archer, who met Demachy in his creation lab, is fragrance flowers producer at Florapolis. Here, farmers don’t use machines nor pesticides to grow, maintain and pick their orange blossoms.

The food industry began investing in organic practices decades ago, and saw how a crop’s growing conditions affected the end product. The perfume industry has started recently. In flower cultivation, these methods, in fact, guarantee an improvement in the yield, and the quality of the flower benefits.

The first day of jasmine harvest at Le Domaine de Manon falls in September. Carole Biancalana, fragrance flowers producer at the estate, describes her encounter with Demachy as the meeting of a lifetime. The two met at the World Perfumery Congress, held in Cannes in 2006.

After the conference, a man came to talk to her. «I make perfumes and I am looking for raw materials to bring them to the heart of my creation. I would like to start with flowers from Grasse and I would like to embark on this journey with you». He showed Biancalana his business card. That’s how she found out he was the Perfume Creator for Dior. As they spoke about the harvest, organic production, and everyday life in Grasse, she realized they spoke the same language and shared a respect for raw materials.

Dior Nose: Harvesting roses in Grasse

In Grasse, rose centifolia owe their quality and resistance to the farmers’ technique in handling them, which they matured thanks to years of experience. Rose buds contain a rose’s genetic information, and are the part of the plant that ends up growing. They are extracted and inserted in the planted rose’s stem.

Each August, a new centifolia sprout is born and the shrub rose is weakened, so that it gets the necessary sap to grow. It is a procedure that must be done for each bush. At Le Clos de Callian there are twenty-thousand rose bushes. This means workers have done the operation at least twenty thousand times. But a rose’s lifetime is fifteen years, and its resistance derives from the mother plant’s health.

When May comes, it’s harvesting season for rose centifolia at Le Clos de Callian. Armelle Janody, fragrance flowers producer, embarked on her journey into floral agriculture with Rémy Foltête. Both come from families of farmers. As their project began, Janody followed Biancalana in the digging, tying, cutting and harvesting. Janody met Demachy at her estate. At the time of his visit, which was caught in a downpour, they had planted seven-hundred rose bushes about twenty centimeter high. A garden-sized field for a grower. But Demachy called back, and their collaboration began.

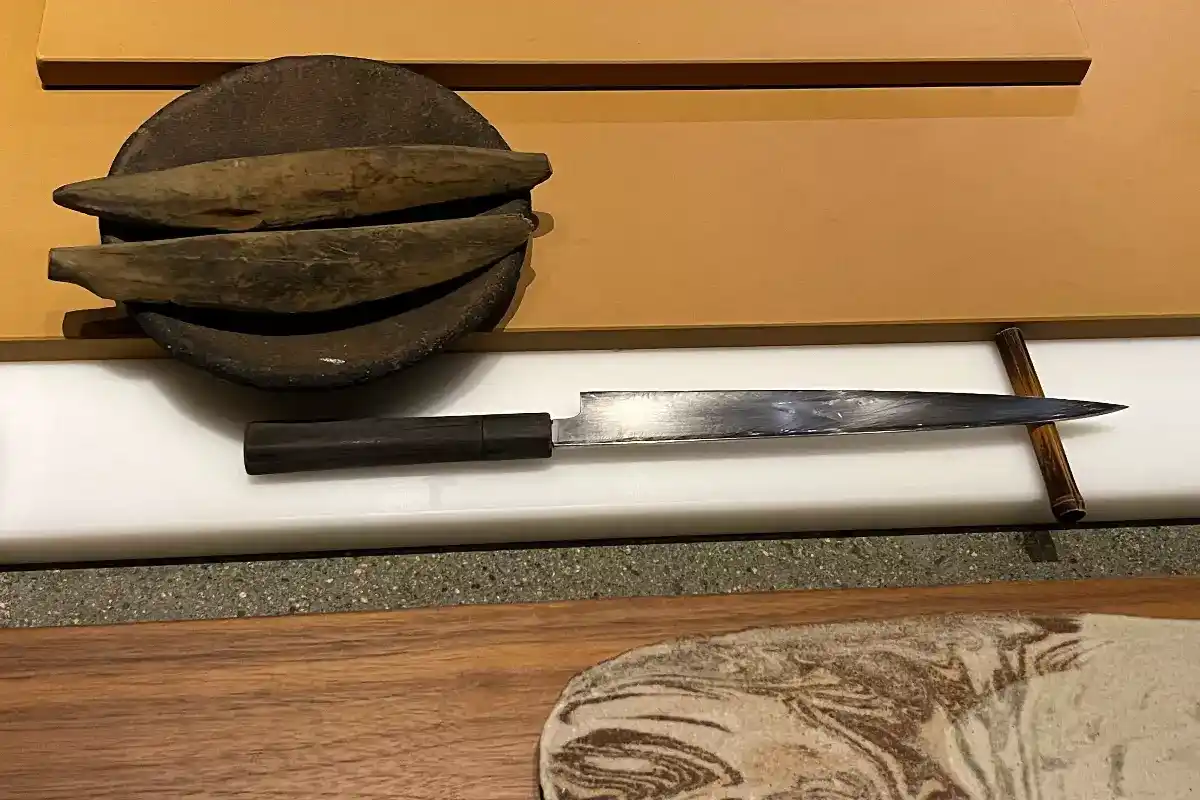

Dior Nose: Robertet’s raw material processing factory in Grasse

Humanity has always tried to capture scents in a physical form. In the twenties and thirties the process of fragrance extraction began to take shape. The plant was treated with a solvent to extract its olfactory components. But it’s distillation that allows to capture the quintessence of smell.

At Robertet, a raw material processing factory, production director Robert Sinigaglia gained his familiarity with orange trees, jasmine, and roses during his childhood and youth thanks to a lineage of growers. At nineteen, he was assistant to the grandfather of Robertet’s patron, Philippe Maubert. September 2019 marked his sixtieth year with Robertet.

The factory’s facility represents Grasse’s history. Here, perfumers receive the knowledge garnered over decades of raw material processing. The aim is to allow them to retrieve the smells they remember, which have not changed in Grasse. The iris roots planted by the team at Robertet take three years to be used for transformation. After that time has passed, they clean and trim them.

Grasse’s manufacturing process

Then, after the iris is cut and dried, its weight reduces by three quarters. Two and a half years must go by before they can be treated by grinding and distillation. From a ton of irises they get three kilos of butter, or three-hundred grams of irone, which are the result of the oxidation of triterpenoids in dried rhizomes of the iris species. «You start with a truck filled with four tons of fresh roots and, seven and a half years later, you end up with three-hundred grams of irone», jokes Sinigaglia.

It was the invention of perfume extraction with hexane, a solvent which allows the treatment of plants while preserving the quality of the flowers, that led the sector to grow. Grasse’s manufacturing process happens in two stages. The extraction of the vegetable raw material or biomass with a volatile solvent, by supercritical fluid or enfleurage, in order to obtain a floral ointment called concrete. And the transformation of the primary extract into absolute through alcoholic washing, glazing, filtration, pre-concentration and final concentration under vacuum.

The perfume industry in Grasse

According to Prodarom’s data, the perfume industry in Grasse comprises sixty-four companies with around four-thousand-and-six-hundred employees and a turnover of 2.9 billion euros. Out of a population of 50.937 inhabitants, fifteen-thousand people make a living from the perfume business, and the agricultural areas dedicated to perfume plants cover more than one-hundred hectares.

Ingredients from Grasse are twenty to twenty-five times more expensive than those sourced from other locations. One kilo of rose centifolia absolutely costs twelve-thousand euros, compared to the three-thousand needed to buy an absolute from a Turkish rose. The richness and fragrance of Grasse’s flowers is due to the terroir on which it grows.

Les Fleurs d’exception du Pays de Grasse, a non-profit association

It was 2006 when Grasse’s producers came together under the banner of Les Fleurs d’Exception du Pays de Grasse, a non-profit association, to promote their terroir’s olfactory heritage. Fourteen years later, in November 2020, the National Institute of Industrial Property (INPI) approved a new geographical indication. L’absolue Pays de Grasse, a recognition of the craftsmanship and quality that belongs to the region. To obtain a fragrance, in fact, a concentrate called absolute, or absolue, an essence is extracted from flowers. It is this element of the transformation of flowers into perfume that has obtained the approval of the INPI.

This success is an illustration of French expertise in perfumery. But it was the producers’ capacity for mobilization and ambition that allowed them to obtain this certification. The association’s interest was to protect Grasse’s know-how, present in Grasse for generations. They are now in charge of the management and defense of the geographical indication.

Grasse’s inscription in UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage list

Back in 2018 Grasse obtained the inscription of its know-how related to perfume in UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage list. A distinction that covers the cultivation of the perfume plant, the knowledge of raw materials and their transformation, and the art of composing perfume.

Grasse relied on this appointment to better protect its tuberose and jasmine fields from land pressure, the rise of synthetic products and competition from other production centers for the last seventy years. The label acts as an encouragement for perfume houses to sign long-term contracts with producers, guaranteeing they can live off their crops.

Grasse farmers and perfumers’ philosophy and vision

When flowers are in bloom, myriads of aromas and colors surround Grasse’s producers. But, throughout the rest of the year, their work is that of the farmer. This is based on restoring and perpetuating the area’s cultivation techniques through observation and common sense, and by dedicating the necessary time to perfecting each detail. Workers live and work in synchrony with the earth’s rhythm, with the flow of time and the cyclicity of the seasons.

Farmers and perfumers hold in common this area’s productive philosophy and agenda’s vision as well as the intention that follows it. To valorize the image of a product through its territory, local varieties, and traceability, while respecting the environment and Grasse’s land workers. In Grasse, craft signifies quality.

Communities pass down the savoir-faire that distinguishes the region, over generations. From plant to product, in fact, the people who cultivate it, preserve it and transmit it every day share the knowledge. To be able to see Grasse’s reality – who is behind the rose, the creation of beauty, and people’s honesty – makes one understand the origin of its quality.

Dior Nose

Dior Nose documents two years of François Demachy life. It opens with the silver-haired star visiting patchouli plantations in Sulawesi, Indonesia. It then hopscotches all over the world as he scouts bergamot in Calabria, ylang ylang in the tiny island of Nosy Be in Madagascar, sandalwood in Sri Lanka, and even ambergris. Digestive matter from sperm whales – yes, you read that right – which has a sweet, musky scent that Demachy calls «mysterious and magical» along the County Clare coast of Ireland. Home base is between Paris and Grasse, the epicenter of French perfumery. Here, growing up, Demachy honed his olfactory sense amid plush fields of jasmine, tuberose as well as rose de Mai.